When Push Comes to Shove: What Was the "Othismos" of Hoplite Combat?

Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte

Bd. 58, H. 4 (2009), pp. 395-415

Published by: Franz Steiner Verlag

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25598486

Bd. 58, H. 4 (2009), pp. 395-415

Published by: Franz Steiner Verlag

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25598486

10.2307/25598486

And later in the book Storm of Spears:

There are serious flaws with his analysis and even more with his presentation. He contacted me early on in his studies, and in the interest of full disclosure I must tell that myself and few others attempted to steer him away from the mistaken path he was on.

I have been largely away from Ancient Greek topics for over a year now due to other demands on my time, but now that I have come back I am finding far too many online discussions where his portrayal of hoplite combat has taken root. I am loathe to enter into what must be a deconstruction of his thesis because he is a dedicated reenactor of ancient hoplites. For years I have been suggesting that he is exactly the type of researcher that those writing histories of Greek combat must heed. Reenactment can be, when done well, experimental archaeology. When it is it must conform to the ethics of a scientific experiment and honestly assess alternate views. In this Mathew's work fails. I assume these are honest mistakes, scientists make them all the time, but the bias he brings to his analysis is all too glaring in his presentation.

When his book came out, the general consensus I received from the many hoplite reenactors I correspond with was that the analysis in Storm of Spears was flawed based on their experience and his notions failed to convince the hoplites at the Marathon gathering. I had hoped that by now members of these other groups would have shot down the mistaken ideas, but I see now that perhaps they do not have the reach to disseminate their ideas as efficiently as Mathew does. I am not sure that I do either, but I will give it a try.

Before I step into the debate, here is an assessment of Mathew's use of percentages of vase depictions as evidence for the exclusive use of an Underhand grip for the hoplite spear. The author is my friend Fred Ray, who has written some really interesting books on hoplite battle. If you are reading this blog, then you should give them a look:

http://www.amazon.com/Land-Battles-5th-Century-Greece/dp/0786467738/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1412604879&sr=8-1&keywords=Land+Battles+in+5th+Century+B.C.+Greece

http://www.amazon.com/Greek-Macedonian-Land-Battles-Century/dp/0786469730/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1412604879&sr=8-2&keywords=Land+Battles+in+5th+Century+B.C.+Greece

I will note that I have no financial tie to these books, but I did give some advice on certain topics.

Here is Fred's review that her was kind enough to share with us on Hollow Lakedaimon:

Storm of Spears (2012, Pen & Sword Military) by C. Matthew:

Some Observations Regarding the Analysis of Artistic Images

Matthew’s analysis of

artistic portrayals in support of his core theory that hoplites within

classical phalanxes did not normally engage in shock combat using over-arm

strikes with their primary weapon (the thrusting spear) appears to be

fundamentally flawed. One can readily accept his contention (p. 20) that

a majority of the figures evaluated (an estimated 243 [71%] out of a sample of

340 in which the grip could be determined) show a weapon with a centrally

located point of balance. One can also easily buy the assertion (p.

21-23) that these devices are much more suitable for throwing than the sort of

thrusting spears designed for shock combat that were common to classical

phalanx battle. These latter favored a rearward grip (p. 8-11).

Such ideas find further backing from the information cited on length in

which the data sub-set of weapons held overhead (and dominated by central

grips) has a notably shorter average (p. 23-24). This is consistent with

devices that can be thrown effectively and contrasts with longer averages for

sub-sets dominated by weapons having rearward grips and therefore better suited

to thrusting (p. 14). The observation offered that sauroters best

associated with simple thrusting spears (p. 4-5) are more common on images of

longer/rear-grip weapons (p. 22) also backs this argument. Matthew’s

proposal (p. 31-33) that a majority of the images in the artistic record

portray archaic or mythological figures using weapons other than single-purpose

thrusting spears thus appears sound. However, while this bodes well for

his contentions (p. 23, 38) that past evaluations treating these weapons solely

as thrusting spears are likely in error, it does not lend support to his linked

assertion (p. 38) that essentially all fighting with the thrusting spear

used under-arm methods. Indeed, the image data presented actually appear

to disprove that particular concept.

Accepting that an apparent 243 (86% of the 60% fraction held over-arm plus half

of the 40% fraction held under-arm [p. 16]) among useable images involve

center-grip weapons other than those traditionally employed in classical era

shock action, only analysis of the remaining 97 figures (those with rearward

grips indicative of a single-purpose thrusting spear) are relevant to the

frequency of hand-to-hand techniques used by classical Greek spearmen. Of

these, 29 (30%) display an over-arm grip while 68 (70%) show an under-arm

grip. Given that an over-arm grip would have no real value outside of its

possible employment in shock combat, every image showing that approach with a

simple thrusting spear (unsuitable as a missile) must therefore have been meant

to portray a man engaging in (or preparing to engage in) shock fighting.

But figures displaying an under-arm grip could well be doing something else -

advancing while putting minimal stress on the spear-arm or resting that arm

during a lull in battle for example. This meshes with Matthew’s

simulation data (p. 122-125) that shows an under-arm pose to be less tiring

during combat. Also agreeing, if we discount the possibility (though it

is strong in my opinion) that the antique, center-grip weapons might be

dual-purpose spears useful for shock combat and are instead solely missile

weapons, is that those 68 figures holding center-grip weapons under-arm (28% of

the center-grip total) must be resting their throwing-arm in a similar

fashion. This means that we can count only those figures with an

under-arm grip that are also shown in the very midst of a shock fight as

truly secure examples of under-arm thrusting. Unfortunately, we are given

no value for this (or a table of rawer information from which it might be

derived).

As a result, given only

the image data provided by Matthew, one must conclude that an over-arm

technique for shock combat appears at least 30% of the time (that value being

the case should all of the images with under-arm grips describe ongoing

shock actions). And this could rise to as high as 100% (in the highly

unlikely case that none of the under-arm images show ongoing shock

actions). Therefore, with a technically possible 30-100% range for its

portrayal, the over-arm method for spear-fighting appears to find rather

convincing support within the artistic record as presented by Matthews, instead

of being completely ruled out as he asserts.

If we reject for

argument’s sake that some (or all) of the center-grip weapons in the images are

multi-purpose spears and assume them to all be missile weapons (“javelins” per

Matthew’s terminology), then we might use them as an analog for a more

refined guess at the likely percentage of over-head thrusting on display.

There are 243 images with mid-shaft grips and 68 (28%) of them are under-arm

poses not suitable for missile combat (where one could not throw the weapon in

hand). This suggests that only 175 (72%) of these images truly represent

men actively engaging at the instant shown. If the same ratio is applied

to figures with thrusting spears (rear-grip weapons), we can calculate that 41

among those shown in under-arm poses are also engaging in shock action.

(This adds that under-arm fraction to the 29 in over-arm stances suitable

for nothing but shock combat to reproduce the 72% share of combat stances in

the center-grip analog.) This would mean that there are 29 figures (40%

of the rear-grip total) making over-arm strikes and 41 (60%) striking under-arm

(interestingly, a mere inversion of the 60/40 ratio in favor of over-arm use

cited by some in considering that all images were showing shock combat

poses). Of course, before taking this kind of estimate “to the bank,” one

must again remember that it excludes all consideration of dual-purpose spears

being on display. Also, it must be viewed in the context that of the 480

figures initially studied by Matthew, only 340 (71%) provided useful

data. These were then reduced to 97 (20%) potentially relevant to the

specific question under review and only 70 (just 15% of the original total)

could then be applied to the investigation’s bottom line when all was said and

done. As such, even rather modest biasing of the sample pool by the

forces of chance in rendering 140 (a full 29%) of the original 480 figures

useless (precisely twice the number available for the final calculation) could

well have had quite a significant impact on the conclusions reached.)

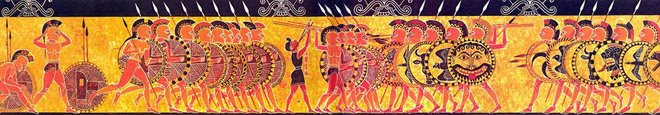

We should further consider that even the foregoing rather more “over-arm

friendly” view of the artistic record might underestimate the frequency of that

method’s true employment. This is because very few (if any) of the

studied images are likely to be portraying the “othismos” stage of phalanx

combat in the “literal” (i.e. physical) sense. Here, hoplites would have

been pressed “belly-to-back” in a manner unsuited for the side-on views

commonly employed in ancient artworks. And an over-arm utilization of the

thrusting spear might well be the most practical method during othismos.

There is wide acceptance that such literal othismos is explicitly referenced in

several of our most detailed descriptions of phalanx battles (per Matthew’s

note on p. 237). And though Matthew considers it rare on the basis of

these being few in number, it remains likely (in my opinion) that similar

episodes of literal othismos developed in a much higher count of more poorly

documented actions featuring similar tactical dynamics.

- Fred

Ray

8 comments:

Hi, I'm interested in what your opinion is on the experiments done on overarm and underarm fighting that he conducts using re-enactors and volunteers. While I may have complaints about his methods and his use of the artistic record, his results show a huge advantage to using the underarm technique in terms of strength, stamina and accuracy while it displays a huge number of disadvantages to using the overarm technique. Along with that he shows a basic mechanical implausibility of switching grip method within any formation other than widely spaced open order?

Hey, thanks for commenting. I am going to do a few posts that will address much of this after I get the grades for my classes in, but I will give you some brief answers.

As to his take on over vs underhand, his technique is flawed. I knew this from the description of such strikes. He seems to believe that overhand blows must be descending, but this is a fallacy. Done correctly, overhand strikes can have a flat trajectory or even hit above the level of your own head. What they did was grip the spear shaft too tightly, leading to a stab like you would make with an ice pick. The proper thrust, in my opinion, is far more like the throwing motion. As I will show, all his complaints, from loss of reach to fatigue evaporate when this is done right.

Overarm strikes are far more powerful than the high-underhand he advocates, and some of us warned him of this long before he wrote his book. This was shown earlier in a laboratory study by Connelly et al. That he conveniently failed to cite. This coupled with the way his figures misrepresent his "close order" as 45cm, when it is obvious from his own figures that this is more like 60cm, are enough that I would have held up publication if I had reviewed this as a scientific publication.

The question of how they switched grip is a red herring, because they never did switch grip. More than one reenactment group has discovered how hoplites lowered their spears from resting on their shoulders directly into an over hand grip. There is some video of the Koryvantes group doing this online.

I will post soon and show his fallacious illustrations and how hoplites carried, brandished, and used the dory.

Thanks for the response, looking forward to more articles from you. I'd love to see the video if you happen to know where it is, I'm having trouble working out the mechanics in my head and it'd be great to see it in action.

Hi. Have you seen the youtube videos of re-enactments? There are two very excellent videos by Thrand, demonstrating the overhand thrust made with a gigging motion. Not just a regular stab thrust, but nearly throwing the spear - but not losing it.

This multiplies the penetration power by many orders of magnitude, due to the high acceleration.

I think the experiments he has done, in these two videos, is far more convincing than the entire book "Storm of Spears", dedicated to the statistical analysis of artistic depictions. Also, I am certain that the dagger-stab thrust of the overhand approach was rarely used, as it is inefficient.

Observe the two videos, and decide for yourself.

Thrand has a background in Mixed Martial Arts, jiujitsu, ninjutsu, fencing, etc.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KtIPp-m69BY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6LaSKE57rZA

John,

I have been commenting on Thrand's thread since he started testing overhand. His rediscovery of what he is calling gigging is an excellent demonstration of why overhand strikes are more powerful than underhand. As I have been writint for years now, overhand engages larger muscle groups and most importantly allows a longer range of motion and time the hand is accelerating the shaft.

I think what he is calling gigging is a technique that has been used historically- maybe even by early hoplites with dual-use spears. There are spearmen among the Moros of the Phillipines who look very like hoplites with a long spear and double-grip shield. Their spears are thick near the head and taper towards the tail. I can't see how these are optimized for anything but gigging.

That said, I do not believe that classical hoplites used this technique. The dory tapered towards the point and was balanced to about 30% from the rear. If those of us who believe this shape are correct, the spear was ill suited to actual gigging. The closer to the rear you grip a spear the less you gain by letting it slip through the hand. The leather grips on some vase depictions would also speak against this.

But the motion and the power are exactly the same whether you release or not- the acceleration ends when the spear and hand disengage. The strike of a hoplite was essentially a throw with the momentum of the spear accounting for most of the force. But in my scheme they did NOT let go of the shaft, though the dory was not gripped tight and it did rotate in the hand to stay on a level trajectory.

It amazes me that Christopher Matthews faulty theories and flawed methodology still find support and that here and on sites like RAT, people who are relatively ignorant of the subject make wholly incorrect assertions.In fact so many that one simply doesn't have time to refute them all. Like Paul B. I am another who tried in vain to help Christopher M. before his thesis was published. I won't plunge into the debate - plenty of others can do that.

I will take this opportunity to introduce a new facet. It has often been hypothesised that the purpose of the sauroter was to act as a 'counterweight', and that shafts were tapered, both with the object of increasing reach. Yet the vast majority of the iconography shows untapered shafts, and even more significantly, the Dory held around it's mid-point.

The 'counterweight' theory falls down completely when you examine actual examples, and realise that they are hollow, not solid ! This of course is consistent with the central grip on an untapered shaft.

In fact there are examples of counterweighted 'sauroters', where a weight has been fairly crudely added externally to the sauroter, so some hoplites at least experimented with this. But the point is, this was not the norm, nor typical.

Hey Paul, great to see you! I've come to the opinion that the spear varied much more than the shield over the period where we can identify hoplites in iconography. I find it quite possible that they were carrying two spears, at least one for throwing, well into the Archaic period. I do believe that the hoplite was armed with a single doru, or war spear of about 8' long. There is enough evidence from the incidences of "grips" drawn at the bottom third or quarter of the shaft of the spears on vases to make this at least a strong possibility. But as you so often pointed out in the past, there must have been a lot of variation both in time and space. Enough that pinning down everything seen with an aspis on vases to a single weapon type is unlikely.

Fred Ray and I have a book going to press next week, "Hoplites at War: A Comprehensive Analysis of Heavy Infantry Combat in the Greek World, 750-100 bce" You figure prominently in the acknowledgments. I finally got a chance to get 40 some hoplite reenactors together to test othismos last fall at Marathon.

Thanks For posting...

quickbooks enterprise support phone number

Post a Comment