“Footwork in Ancient Greek Swordsmanship”

Brian F. Cook, Metropolitan Museum Journal, Vol. 24 (1989), pp. 57-64

In this paper an overhead strike is discussed. With minor variations it appears as below.

From the paper:

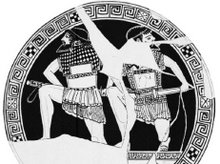

“The so-called "Harmodios blow" studied by Shefton, who coined the useful term by which it is now fairly generally known. This is a slashing movement named for the action of Harmodios in the marble statuary group of the Tyrant-slayers best known from a Roman copy in Naples. The moment most frequently represented is the point of stillness when the sword- hand has been raised head-high with the sword pointing backward over the shoulder in readiness for a downward slash. The blow may be delivered either forehand (Figure 1) or backhand (Figure 2). Philip Lancaster, of the Department of Edged Weapons at the Tower of London, who kindly gave advice on some practical aspects of swordsmanship, pointed out that this movement would be hazardous under normal combat conditions: not only is there some danger that it would put a swordsman off balance, but the action would also leave the sword-arm unprotected and vulnerable. B. B. Shefton had already noted that the sword when raised could not be used for parrying, and that in close combat the blow therefore required careful timing. It would have been particularly dangerous for a Greek hoplite in leaving the armpit exposed above the edge of the cuirass.' A further disadvantage of the Harmodios blow is that it was less effective than a thrust against a well-equipped opponent: it would probably have been resisted even by a padded linen corselet, which would have been vulnerable to a thrust, and would certainly have been ineffective against a metal cuirass." In combat, then, the Harmodios blow can only have been a desperate measure, employed when the vulnerability it imposed was outweighed by a greater danger.”

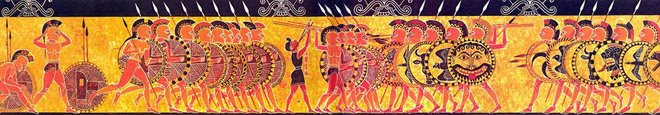

“Finding no examples of the use of the Harmodios blow before the closing years of the sixth century B.C.,' Shefton connected it with the introduction of the spatulate sword, a more versatile weapon than the straight-edged sword, which is most effective in an underhand stabbing or thrusting movement. It is around the same time that warriors began to be represented in Attic red-figure in a stance that, al- though it soon became conventional, may reflect the kind of simple drill-movement for which no literary evidence survives. The movement is in fact so simple that no specific comment was made by ancient authors: like so many minor details of life, it was too familiar at the time to call for explanation.”

Now the above may all be true, but the Harmodios may not have been so dangerous and unlikely as thought by the authors above. In fact the Harmodios blow might be one of the few strikes available to men who are standing in synaspismos, close order with overlapping shields. If men are in close as I have described previously, shield to shield, then the right arm needs to not only strike in this fashion, but also move in this way to ward the head. I have been experimenting with how one could fight in so close, with only the raised right arm given freedom of movement. The answer is very much like the harmodios blow. Better yet would be to adopt a shorter blade like the Spartans may have done.

An interesting note on swords is that the sword (xiphos) is slung in a sheath high under the left arm, almost like a shoulder-holster for a pistol. I have been told by hoplite reenactors that this makes drawing the sword much easier in the confined space of a fighting phalanx. The manner of hanging the sheath may thus be yet another feature of the panoply designed for fighting in crowded conditions.