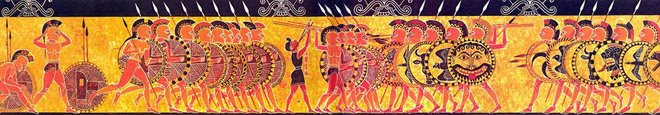

The wearing of a shield on the forearm with a double-grip is not unique, but it is uncommon for an infantry shield. Cavalry gain from having a second hand free to hold reins, and shields that developed out of cavalry shields may retain this feature. Infantry that are expected to bear a two-handed weapon, or peltast skirmishers, who bear javelins in the left hand, will benefit from a double-grip as traditionally seen in the pelta.

It is possible that this was the original explanation for the double-grip in the ancestral aspis, for early hoplites appear to have been armed with two spears: one to throw and one to fight with.

In hand to hand combat there is little to gain from affixing a shield to the forearm and much to lose. A shield on the arm cannot be brought to bear across the body with the facility of a single-grip, one handed shield held. The heavy shield cannot be simply rested on the ground during lulls in combat. It cannot be used as effectively to punch, the forearm shiver being weaker, nor can it hold off a foe at "arms length."

There is an effect of the distance a shield is held from the body which will be familiar to fencers. As shown at left, the increased distance between the shield and body (B) cuts down on the angle of attacks that are able to reach a defender compared to a close-held shield (A). From a protective standpoint The double-grip adds little.

There is an effect of the distance a shield is held from the body which will be familiar to fencers. As shown at left, the increased distance between the shield and body (B) cuts down on the angle of attacks that are able to reach a defender compared to a close-held shield (A). From a protective standpoint The double-grip adds little. If we look at a cross-section of the aspis, we see that it is somewhat dome shaped and the thickness is greater towards the rim than in the center. This is peculiar in a shield because they are normally thickest in the center, providing maximum protection to the core of the body behind them, and taper towards the edges.

If we look at a cross-section of the aspis, we see that it is somewhat dome shaped and the thickness is greater towards the rim than in the center. This is peculiar in a shield because they are normally thickest in the center, providing maximum protection to the core of the body behind them, and taper towards the edges.

These structural elements were not seen in the world of ancient Greece, though they would be common a few centuries later. They are the elements that make up a load bearing arch, such as the Roman aqueduct at right.

If it is an arch in cross-section, the complete aspis is a dome. A dome is the most efficient shape for bearing weight, and, though not seen in ancient Greek architecture, has been a feature of construction since its discovery.

A dome works by transferring force downwards from the apex of the structure to the substrate on which it stands- the ground in the case of a building. The diagram below shows the process of transferring force.

You can see that to function efficiently the dome needs to be rather steep sided. The aspis was not so convex, its shape is called a "shallow dome". Shallow domes do not work as efficiently to transfer force through the structure. They are likely to collapse in the center, simply popping inside out like a pop-top or an umbrella in the wind. Also, because the much of the force is directed laterally instead of down into the substrate, the edges are likely to split as the material is force outward on all sides. Below are some ways in which a shallow dome fails.

You can see that to function efficiently the dome needs to be rather steep sided. The aspis was not so convex, its shape is called a "shallow dome". Shallow domes do not work as efficiently to transfer force through the structure. They are likely to collapse in the center, simply popping inside out like a pop-top or an umbrella in the wind. Also, because the much of the force is directed laterally instead of down into the substrate, the edges are likely to split as the material is force outward on all sides. Below are some ways in which a shallow dome fails.  There are ways to support a shallow dome that can counter this tendency. A heavily reinforced rim will keep the edge of the shallow dome from "kicking out" laterally and prevent failure. reinforcement of the inner face of the shallow dome is accomplished by a truss. In architecture this is usually accomplished by steel cable, but it can be a solid metal reinforcement as well. A truss acts by countering some of the lateral force. By connecting two points in the structure with the truss, the pressure on one side forcing outward will pull the truss to counter the outward pressure on the opposite side. By placing a truss at the point of maximal stress, the structure can be reinforced. A truss placed higher towards the apex will aid in this manner and keep the face of the shallow-dome from collapsing inside out. Diagrammatically I show the truss as a cord or band running across the shield, but a truss can also run around the inside of the structure and have the same effect.

There are ways to support a shallow dome that can counter this tendency. A heavily reinforced rim will keep the edge of the shallow dome from "kicking out" laterally and prevent failure. reinforcement of the inner face of the shallow dome is accomplished by a truss. In architecture this is usually accomplished by steel cable, but it can be a solid metal reinforcement as well. A truss acts by countering some of the lateral force. By connecting two points in the structure with the truss, the pressure on one side forcing outward will pull the truss to counter the outward pressure on the opposite side. By placing a truss at the point of maximal stress, the structure can be reinforced. A truss placed higher towards the apex will aid in this manner and keep the face of the shallow-dome from collapsing inside out. Diagrammatically I show the truss as a cord or band running across the shield, but a truss can also run around the inside of the structure and have the same effect. The aspis displays these features that allow a shallow-dome to bear maximum weight. The first and most obvious is the robust, and more importantly, off-set rim. The rim is off-set to provide the maximum resistance to the force that would cause the edges to be forced apart. The thick wood is enhanced by the common addition of a metal reinforcement. This add the tensile strength of the metal to the structure as the metal resists being stretched outwards.

The aspis displays these features that allow a shallow-dome to bear maximum weight. The first and most obvious is the robust, and more importantly, off-set rim. The rim is off-set to provide the maximum resistance to the force that would cause the edges to be forced apart. The thick wood is enhanced by the common addition of a metal reinforcement. This add the tensile strength of the metal to the structure as the metal resists being stretched outwards.As can be seen in the above diagram, the aspis has a zone near the edge where it becomes steep. This area is particularly vulnerable because the change in angle means that it will bear much of the lateral pressure. Not surprisingly it is the thickest section of the shield.

There are two features which are commonly seen in the aspis that may also support the shallow-dome. There are metal bands seen running around the inner surface of many shields in art, and some examples have been excavated. These bands are too narrow to provide protection from penetration, but are firmly affixed to the shield's inner surface and may act as a truss. They can be seen closer to the apex and at the point of maximal stress near the edges.

There is another feature that is seen on almost all hoplite shields. The grip, or antilabe, is a segment of a chord that runs around the inner surface of the shield through rings affixed precisely where we would expect to find a truss and by running loose through rings would share tension across the shield. The function of this rope is unknown. Images of men apparently using this rope as a sling to carry the shield exist, but the elaborate system, unique the the aspis, seems over-built for this function alone when we consider that the telamon, shield sling, had been around for centuries. Some images show this rope and a separate sling in place. Against its use as a truss is the fact that it is generally shown slack. It is possible that by the date of the images we have the truss was no longer functional, but a decorative holdover from a past functional truss rendered unneeded by better construction techniques and supplementary reinforcements like those above. Another explanation may stem from the fact that the truss cannot be left under tension or the rope will stretch and loosen. Artists painting from an aspis model in their workshop might simply be painting untightened trusses.

There is another feature that is seen on almost all hoplite shields. The grip, or antilabe, is a segment of a chord that runs around the inner surface of the shield through rings affixed precisely where we would expect to find a truss and by running loose through rings would share tension across the shield. The function of this rope is unknown. Images of men apparently using this rope as a sling to carry the shield exist, but the elaborate system, unique the the aspis, seems over-built for this function alone when we consider that the telamon, shield sling, had been around for centuries. Some images show this rope and a separate sling in place. Against its use as a truss is the fact that it is generally shown slack. It is possible that by the date of the images we have the truss was no longer functional, but a decorative holdover from a past functional truss rendered unneeded by better construction techniques and supplementary reinforcements like those above. Another explanation may stem from the fact that the truss cannot be left under tension or the rope will stretch and loosen. Artists painting from an aspis model in their workshop might simply be painting untightened trusses. Such rope trusses were not unknown to the ancient Greeks. they are a common feature in ship construction known as upozwmata. They may stretch across the ships beam as shown at left, or run fore and aft to prevent what is known as "hogging", where the ends of a boat droop in relation to the center. This force on the center is analogous to the force on the face of the shallow-domes above. The Latin term for these trusses, tormentum, implied another feature. They cannot be left tight, but must be twisted tight before a ship sails.

Such rope trusses were not unknown to the ancient Greeks. they are a common feature in ship construction known as upozwmata. They may stretch across the ships beam as shown at left, or run fore and aft to prevent what is known as "hogging", where the ends of a boat droop in relation to the center. This force on the center is analogous to the force on the face of the shallow-domes above. The Latin term for these trusses, tormentum, implied another feature. They cannot be left tight, but must be twisted tight before a ship sails. In the next post I shall show how the fact that the aspis is a load-bearing structure determines the nature of hoplite combat.

2 comments:

Hi Paulus. One criticism: you leave out the obvious advantage of supporting a shield on your forearm and shoulder or neck- that it reduces the strain on the arm. Clearly its much harder to support a 15 lb shield for an hour at the end of your arm than it is to support it close to your body and resting on your shoulder. The Roman scutum shows that this isn't an unsurmountable problem, but it is significant.

To anyone who's been in a serious fight, the answer seems clear. Try it. A shield rigged like that becomes, amongst other things, a surprise, short range chopping edge. The extra weight on the rim adds to it.

Surprise your foe by smacking him in the face with the edge of your shield.

Post a Comment