I received the OK from Jasper at Karawansaray Publishing to post my full article on hoplite mechanics as it appeared in the Marathon special issue of Ancient Warfare

: http://www.karwansaraypublishers.com/shop/the-battle-of-marathon-special.html

Over the last half

century, a schism developed over hoplite combat that has devolved into a bellum sacrum, with an orthodoxy assailed

by an increasingly popular heresy. The

orthodox position, championed by Hanson, Luginbill, and Schwartz, portrays

hoplites as lumbering masses of men that charged directly into each other and

contested the battlefield by attempting to physically push their foes. Van Wees, Krentz, and Goldsworthy, describe

hoplites as closer to skirmishers, fighting in an opened order, and often

paired with missile troops. Any “push”

was either a figurative description or uncoordinated shield-bashing. I believe they are both in some measure

correct, and often equally wrong, because this debate has forced historians to

stray far from their fields of study. Their

arguments suffer from an insufficient understanding of the physics and

mechanics of large masses or crowds. Group

behavior is my field, and, with the context that I can provide for their

arguments, I shall make an attempt at syncretism.

Herodotus, writing in

the mid 5th century, was the first author to describe the heavy

infantry of ancient Greece as hoplites, or men who were considered fully equipped

for battle. In his day, a hoplite’s arms

and armor, his panoply, might have included a bronze helmet, greaves, a bronze

cuirasse or corslet of leather or textile, and an iron sword. A rich man might add bronze thigh, upper arm,

ankle, and even toe guards. The only

pieces that seemed to have been required were the large, round shield or aspis and

a 1.8-2.5 m thrusting spear. Herodotus

contrasts hoplites with psiloi, literally “naked”, armed with missile

weapons. By the time Herodotus wrote, hoplites

fought in a formation termed a phalanx by modern authors, following Homer’s use

of the term in relation to massed combat.

The panoply of the

hoplite emerged in the late 8th century, with the advent of the

round, domed, shield and thrusting spear with pointed spear-butts, or

sauroters. It has been suggested that

these items indicate a break from earlier, skirmishing and missile combat, but

aspis bearing hoplites on some early vases, like the Chigi vase (ca. 640),

appear to bear a pair of spears with throwing cords attached, a shorter one

most likely to be thrown and a second longer spear which could be thrown or

used in close combat.

By the 5th century, the

classical Greek dory, or fighting spear, appears to have been as much as 2.5 m

long, but it was effectively longer because a combination of rear weighting and

tapering of the shaft moved the center of balance, hence the grip, back to

about a third of the way from the bottom. A 2.5 m dory had a reach of over 1.5 m,

similar to a 3.3 m mid-balanced spear.

The great reach of this spear was a handicap in single combat, because

it would be useless if a foe managed to move up shield to shield. A man cannot reach back far enough to bring a

point that is 1.5 m from his grip to bear with any force against a foe this

close. However, in a battle line, the

extra reach enabled hoplites to overlap their spears and support the men beside

them. Moving within the reach of the

combined spears of a phalanx would be much more difficult than evading any

single spear.

The shield has also

been seen as unsuitable for single combat.

The hoplite’s shield, the aspis, hoplon, or perhaps most specifically,

Argive aspis, varied little in size or shape over the whole period of hoplite

warfare. It was made in the form of a

flattened dome, some 10 cm deep, between 90 cm to just over a meter in

diameter, including a robust, offset rim of some 4-5 cm. The rim, and often the whole face of the

shield were covered in a single sheet of bronze, 0.5- 1 mm thick. The orthodoxy reconstructs this shield as

exceptionally heavy (7-9 kg), but Krentz has suggested a more likely 6.8 kg or

less.

These features are not

unique to the Greek shield. A convex

shape functions to transfer force away from the site of impact, while an offset

rim reinforces the face of the shield so that it does not split when

struck. Exceptionally convex shields,

conical in profile, are common in many cultures because the profile ensures

that an incoming strike will encounter a sloped shield-face.

The aspis had an

uncommon system of grips that some suggest limited the shield’s utility in

single combat to the point that men were forced to fight in close order. The left arm was slipped through a bronze

cuff, or porpax, placed either at the shield’s center or just to the right of

center. The porpax either accepted a

leather sleeve or was itself tapered to accept the forearm up to just below the

elbow, and fit like the cuff of a modern artificial limb, holding the limb so

snuggly that the shield would not rotate around the forearm. A second grip near the rim of the shield was

gripped by the hand, and tension from this grip acted to hold the arm in the

porpax. In shields from other cultures

that have a double-grip system, the grip for forearm and hand usually flank the

center of the shield. This allows most

of the shield to be brought up in front of its bearer, while the aspis allows

only half the shield to cover a man’s front.

The central placement of the porpax in the aspis is an advantage because

it makes holding the shield up on the bent forearm easier by reducing the

proportion of the shield’s mass that is to the right of the elbow and must be

pivoted up. A double-grip limits the

range through which a shield can be moved to block. The shield cannot be held as far away from

the body as one gripped by the hand, which leaves a greater portion of the body

vulnerable to incoming strikes and reduces the distance a strike must penetrate

to wound. It has been suggested that

hoplites could gain coverage by standing perpendicular to shields in a

“fencers” stance. This analogy is

untenable because fencers lead with their weapon hand, while hoplites would

have to come up parallel to their shields to effectively strike with their

spears.

The aspis has one

unique feature that is difficult to explain.

The Bomarzo shield in the Vatican’s Museo Gregoriano Etrusco, which

retains large portions of its wooden core, presents an odd picture. The shield’s core is only 5-6 mm thick over

much of the shield’s face, thickening to 8 mm in the center where the porpax

was affixed. Near the rim of the bowl,

the shield curves back sharply to form side-walls of 10-14 mm that taper

towards the shield face.

A shallow dome tends to

spread outward under pressure, and the wide, perpendicular rim acts to keep the

face from splitting. Under pressure, an

aspis will fail where the side-wall and the face join. This odd profile has inspired the suggestion

that the aspis’s great weight required this curve to allow a man to carry the

shield on his shoulder. Leaving aside

that the aspis’s mass has probably been overestimated, some rough calculations

show that this explanation is unlikely.

The aspis’s weight did not likely motivate the curved outer portion

because, even though only 3-4 cm wide,

the greater thickness and large diameter of the “ring” of wood that

makes up the side-wall section accounts for 20-40% of the total mass of wood

making up the shield-face! Reinforced

side-walls could provide added protection against chopping blows by swords, but

this would be superfluous given the thick, bronze covered rim. The side-walls appear to add more depth to

the shield than strength, a function we will return to later.

Modern authors present

us with irreconcilable images of how these early aspis-bearers fought. To some there was a “hoplite revolution” and orderly

phalanxes either closely follow or predate the new shield. Van Wees describes a “motley crew” of

intermingled hoplites, archers, and horsemen that slowly transitions from bands

of warriors to the phalanx familiar to 5th century historians. Tyrtaeus, a 7th century Spartan poet, wrote

to inspire the warriors of his polis.

Two themes run through his works: he chides his audience to stand close

to their fellows and to bring the fight to close quarters with their foes. Tyrtaeus can easily be interpreted as a

herald for the classical hoplite phalanx, with close ordered ranks and files. But if men were formed in an orderly phalanx,

why would the poet need to deride skulkers who remained out of the range of

missiles?

This dichotomy of

order-vs-chaos is a hot topic in the physical sciences, and the boundary

between the two has diminished. Order

within groups can arise spontaneously from seemingly random acts of individuals. We call this process self-organization. Through this mechanism, swarms, flocks, herds

and schools of animals achieve levels of coordinated movement that any human

drill master would envy. Swarms, or

crowds, of humans are capable of this type of organization as well. If we take van Wees’s “motley crew” and add

simple, logical rules like “archers tend to stand behind men with shields” and

“men with shields tend to stand beside men with shields to protect their flanks”,

then we end up with a formation that resembles the Germanic shield-wall or late

Roman foulkon. This type of formation

puts more heavily armored men, who may throw missiles themselves, in front of

unarmored missile troops to act as a wall or screen. Segregation like this is

natural in tribal war bands, where richer, better equipped men lead a troupe of

progressively poorer equipped warriors into battle. It would actually take more discipline to

keep troop types evenly mixed than to clump in this manner.

There is no need for

hoplites to form in a particularly opened order to allow men to move freely

through such a self-organized group. One

advantage of the large diameter of the aspis is that it acted as a literal

meter-stick. Men did not need to make

any judgment on their frontage beyond lining up shield rim to shield rim. In human crowds, as in schools of fish or

flocks of birds, individuals are completely interchangeable. The result is that

no one has a specific place in the formation and the group is highly

fluid. Men can move to the front line or

beyond to throw missiles at the enemy or challenge a foe, then melt back into

the group and retire out of combat. Such

“milling” is commonly seen in all but the densest of crowds.

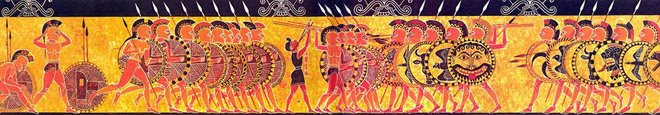

When two crowds come

into contact, the dynamic changes and the presence of one lends order to the

other. The limitation on forward

movement and the presence of the enemy line as a focal point for the men in

both mobs results in the crowd becoming denser as men pile up. If the men at the front-line between the

groups are shield to shield, then the literal pushing of mass on mass

envisioned by the orthodoxy could ensue.

Thus, a crowd like this can be both flexible enough to allow all of the

missile combat and personal challenges seen in the pre-hoplite era and

spontaneously form into compressed masses akin to phalanxes upon contact with

the enemy. Men who are free to move

forward and back are also free to flee at the first setback. This can be mitigated by forming men up next

to their relatives or in smaller units, where leaving would be noticed. To form the ordered ranks and files that made

up the classical phalanx, each man needed to know only who he stood next to or

behind

If the economies of the

Greek cities allowed for increasing numbers of warriors and a higher percentage

of these were well armed hoplites, then a shift from a few ranks of men acting

to shield lighter troops to deep ranks of spearmen who charge swiftly to spear

range may simply emerge from the conditions of the battlefield rather than

result from an intentional tactical shift.

As the number of men increased, additional depth would be easier to

coordinate than a widely extended battle line. If the percentage of missile

troops dropped low, or the defenses of the hoplites reached a level of

protection that charging through an enemies’ missile barrage was less risky

than engaging in a missile duel, then the move to an all hoplite phalanx would

result. Once hoplites began to form in

more than four ranks, missile troops became ineffective. Xenophon (Anabasis 3.3.7) describes the

difficulty of bowmen in firing over the ranks of their own hoplites.

Increasing the depth of

phalanxes is advantageous in close combat for a variety of physical and

psychological reasons. The heretical

view holds that the ranks beyond the first one or two do not directly

participate in battle, but play an important role in supporting the front ranks

in battle. Beyond acting as a reserve,

ready to step forward over the fallen rankers in front of them, the mere

presence of these men behind the front rankers raises the morale of those men

fighting. In addition, deep ranks of men

formed behind the fighting front limit the ability of those men to turn and

run.

In orthodox view, all

of the ranks run together into battle as a single mass, then crash into the

formation of their foes. This physical

pushing match, for which the term othismos has been applied, has been likened to a giant rugby scrum, with

the goal of pushing the opposing section of the phalanx out of alignment with

the rest of the formation until they rout.

I believe that a pushing match did occur in hoplite battle, but I am

sympathetic to the heretics because the physics of othismos have been misstated

by the orthodoxy.

Othismos was a noun

that derived from the word otheo, a verb meaning “to thrust, push, or shove”. The modern definitions of othismos treat the

noun othismos as a verb, for example Liddell and Scott render it as either

“thrusting, pushing” or secondarily “jostling, struggling”. As a noun, the word would have to be defined

as “a state wherein thrusting, pushing, jostling or struggling occurs”. We commonly call such a state a dense

crowd. Perhaps the best English

equivalent would be the way we derive a state of dense crowding, a press, from

the verb “to press”. This is not a crowd

in the sense of many people or a throng, because the Greeks had other words to

describe that. It is essentially a

traffic term, like jam or deadlock, implying that many individuals are locked

together and cannot move past. Crowds

can “push” with extreme force, but the word focuses on density, more of a squeeze

directed within the group than without.

The term “Othismos” had

three common uses. First, it is used to

describe hoplite battle. Thucydides (4.96.2)

describes fierce combat, noting that it is accompanied by “othismos

aspedon”. This description has been held

up as the clearest evidence for othismos as “pushing with shields”, but perhaps

a better reading is a “deadlock of shields”, emphasizing the crowding of the

opposing ranks together, with or without pushing. Arrian (Tactica 12.3) used the same word to

describe not opposing ranks, but the crowding of second rankers in a phalanx

against the backs of the front rankers, after which they can reach the enemy

front rankers with their swords.

Second, othismos is used is in situations

familiar to anyone studying crowd disasters.

In the worst of these, people are asphyxiated or squeezed either hard

enough or long enough to cause them to lose consciousness or die because

pressure on their chest and diaphragm prevents them from breathing. Xenophon (A. 5.2.17), Plutarch (Brutus 18.1),

and Appian (Mithridatic wars 10.71) all describe othismos occurring as a crowd

of men attempt to exit a gate. Polybius

(4.58.9) describes the Aegiratans routing the Aetolians who fled into a city:

“in the confusion that followed the fugitives trampled each other to death at

the gates…Archidamus was killed in the struggle and crush at the gates. Of the

main body of Aetolians, some were trampled to death…” It is a maxim that most deaths attributed to

trampling are in fact due to asphyxia while still standing.

The third use of

othismos occurs where literal pushing could not occur. When Plutarch (Aristides 9.2) describes ships

in othismos, he refers to crowding, not mass pushing. In many cases, “othismos” is completely

figurative. Herodotus twice (8.78, 9.26)

uses othismos to describe an argument. This

is often translated as a “fierce argument”, but traffic terms are commonly used

to describe arguments. For example, we

regularly call for an arbiter when two sides in negotiation come to an impasse

or a log jam. At Plataea, the Tegeans

and Athenians (Herodotus 9.26) found themselves at an impasse in negotiations

because they both put forth equal claims to an honored place in the army’s

formation.

The definition of

othismos does not of itself require a coordinated push of all ranks against an

enemy formation, but I believe there was such a concerted struggle of mass

against mass. The orthodoxy portrays

hoplites as charging as much as 50 m in order to impart what Schwartz termed “a

maximum of penetration power at the collision”.

However, the whole notion that hoplites charged like un-horsed medieval

knights to maximize the mass’s force during a collision is a fallacy. It takes only a few yards to achieve “ramming

speed”, and any excess distance causes fatigue and loss of cohesion. They would

be correct if the goal was to maximize the force of one man colliding with

another, but the physics of maximizing the aggregate force of a group of

individuals is different. Dense packing

is far more important to transfer a strong, sustainable force, even if it

occurs at slow speed. If a hoplite

phalanx charged directly into a pushing of match, it would have closed up all

of the men in the files belly to back in the manner I have previously described

(Bardunias 2007) and charge from very short range to minimize the loss of

cohesion.

The common description

of othismos as a tug-o-war in reverse leads to some false impressions. The image conjures up men standing

perpendicular to their foes, digging in the edge of their rear foot as they

lean into the man in front with their shoulders in the bowls of their

shields. But in a tug-o-war, the force is

transferred through the rope and men can take any stance as long as they pull

on the rope. This is not the case with

files of men pushing. As men in files

pushed against those in front, the force first acted to compress the men in

front, and only after they resisted compression could force be transmitted

ahead. At moderate levels of compression

this was not a problem, but as greater force was transferred forward, the men

could no longer hold their shields away from their bodies and shields became

pressed to the torsos.

If men were standing in

a side-on stance as portrayed by the orthodoxy, the force would be transferred

directly through the shoulders of each man in file. This was unstable because the only thing

holding men perpendicular to their shields was the strength of their left arm. Unless the men closed up laterally belly to

back, which is impossible with a meter-wide aspis, the sustained, grinding

pressure on their right shoulders would force them to collapse forward until

they were parallel to their shields and the men in files were packed belly to

back. Once they achieve this spacing and

stance, they can be compressed no further and have achieved what specialists on

crowd disasters term a “critical density”.

This is defined as at least 8 people pressed together with less than 1.5

m of spacing per person. By simply leaning against the man in front like a line

of dominoes, 30-75 % of body mass can be conveyed forward in files, and just

three leaning men can produce a force of over 792 N or 80 kg. Shock waves can travel through such crowds,

and less than 10 people have been shown to generate over 4500 N or 450 kg of

force.

This has been misunderstood

by authors in the past. To counter the

objection that the force transferred forward by men in files would be lethal to

one’s own file-mates, Franz, as quoted by Schwartz, mistakenly put forth that

force is not derived from the weight of them men in file, but from their

muscular strength in pushing. This is

not true. He further quotes Franz as

describing why the files did not produce lethal pressure: “When people behind

sense that pushing does not produce an immediate advantage, they stop

pushing. This results in a kind of

reverse thrust.” This is surely true for

most historical armies, where weapon play, not pushing is the goal, but the

whole point of othismos as defined by the orthodoxy is to push against the

opposite formation with the greatest force.

A file of hoplites, even 8 deep, could produce enough force to kill a

man through asphyxia. A force of 6227 N

will kill if applied for only 15 seconds, while 4-6 minutes of exposure to 1112

N is sufficient to cause asphyxia.

Hoplites would be purposefully attempting to create and maintain levels

of pressure that occur accidentally in crowds.

Killing crowds form when people try to move in a specific direction,

such as towards a stage or out a door.

Hoplites pushed ahead in file, and if whatever was in front of them did

not give way, pressure would rapidly build to lethal levels, and by simply

leaning forward they could maintain much of this force for extended periods.

There is no requirement for containment such as walls alongside the crowds as

we usually see in disasters. As long as

they are pushing towards a common goal, in this case directly toward the enemy

through the back of the man in front, they will not disperse laterally.

The heretics would be

correct in assuming that pushing by deep files was not survivable, but for one

detail. In my description of the hoplite

shield, I put off discussing the single feature of its construction that

appears to be unique - the oddly thickened side-walls. As I noted, it appears to primarily add

depth, not strength, when compared to other convex shields. It is this depth that allows a man to survive

the press of othismos, by protecting his torso from compression. To do so, it would be held directly in front

of the body with the top right half of the shield resting on the hoplite’s

upper chest and the front of his left shoulder, the bottom on his left thigh. Most of the men in files would have been standing

upright and leaning forward. Only the

rear few ranks had enough freedom of movement to assume positions that are

compatible with active pushing. Shock

waves of the combined weight of the file would be added to the pushing force in

the rear rankers in the same manner that the mass of a battering ram is pushed

towards a barrier.

Othismos may have originated

because men pushed their foes away from fallen leaders to retrieve their corpses

and armor. Such struggles are common in

the Iliad, and Herodotus used the word othismos to describe the struggle over

Leonidas’s body at Thermopylae (7.225).

In what may represent an egalitarian shift, victory in hoplite battles

generally went to the force that held the battlefield and the bodies of all the

fallen men upon it. This could represent a ritualization of warfare, and a

means of deciding conflict that minimized slaughter, but it may have been the

most efficient means of combat given a preexisting warrior ethos that called

large decisive battles and the retrieval casualties. Pushing would have evolved gradually from

close-in fighting that predated the aspis.

Mass pushing is not unseen in other settings. For example, the Romans pushed with bosses of

their shields Zama (Livy), but the shape of the scutum limited the maximum

force that could be generated without killing their own men. A sub-lethal, jostling, shoving crowd must

have existed before the aspis became specialized for killing crowds. Also, the threat of battle moving to a lethal

crowd phase would justify the shape of the shield, even if othismos was not the

goal of combat. The shield as “life

preserver” in a killing crowd explains the constancy of the shape over time. The deep, flattened dome could not vary much

and still retain its ability to resist compression. When the shield was found inadequate

protection from missiles, an apron of leather was hung from the round shield

rather than remaking the shield into a weaker oval that would provide the same

coverage.

The remainder of this

article describes the course of hoplite battle in Herodotus’s day, reconciling

orthodox and heretical views where possible.

Athenian hoplites, like those of most poleis, called up amateur levies

according to tribal units called taxeis of about 700-1000 men, which was then

subdivided into lochoi of 100 or more. The

men may have not had set places in ranks, but by this date they probably knew

who they stood next to. These taxeis

were drawn up alongside one another to form what Thucydides called a parataxeis

and others call a phalanx. Spartans provide us with an example of what was

possible with a professional army. Their

basic tactical unit was the sworn band or enomotia of about 40 men, wherein

each man knew his assigned place.

Ancient authors usually recorded the number of ranks, or shields, men

formed in. This seems to have often been

up to the unit commander, and could commonly vary from 4 to 16, with 8 or 12 being

the norm for most of the period.

Environmental constraints, like a narrow road, could force units to form

in deep ranks by stacking smaller units.

Thebans in the late 5th and early 4th century notoriously formed in 25

or even 50 ranks for major battles, an obvious advantage for their contingent,

but their allies attempted to limit them to 16 ranks in the Corinthian war

because the sacrifice in frontage left the whole phalanx vulnerable to

envelopment.

Once the men were in

place, in most armies their leaders would walk along the front haranguing

them. Spartans relied on encouragement

between hoplites and sang to each other in the ranks. In a prelude to the battle to come, the

opposing light troops or cavalry could skirmish in the space between the

opposing phalanxes. When the light

troops had been recalled and the sacrifices had been taken, the commanders had

trumpets, salpinx, sounded and men began marching towards the enemy. At this distance men would have been marching

with their spears on their right shoulder and their shields on their left. For comfortable carry, the balance point of

the spear should be just beyond the shoulder, and many images show hoplites

holding the spear down near the sauroter.

Ancient Greek battle fields were notoriously flat and not overly broad

which allowed men to keep some semblance of order. As they advanced the hoplites sang the Paian

in unison, aiding morale and coordination.

Marching in step would have been beyond most armies, but Spartans moved

to the sound of pipes to help the men keep pace. At this point men would bring the shield up

in front and the command would be passed for the first two ranks to lower

spears. This has been interpreted as

bringing the spears down to an underarm position, but hoplite reenactors have

discovered a simple maneuver to “lower” a dory into the overhand position. They let the spear fall forward off the

shoulder while at the same time bringing the rear of the spear out and up. There would be no need to shift the grip

later if overhand strikes are desired.

When the armies were

less than 180 m apart, most phalanxes shouted an ululating war cry to Enyalius

and charged at the run. They did so for

psychological reasons, both to channel their nervous tension into the attack,

and frighten the enemy with their rapid advance. Coordinating the charge along the chain of

units that made up the phalanx seems to have been difficult, and gaps often

formed as some hoplites charged sooner than others. Variation in speed of advance could lead to

one section of the line leaving the rest running to catch up (Xenophon,

Anabasis, 1.8.18). Spartans did not

charge at the run, but approached in a slow, orderly fashion, so any unit

ranged alongside them invariably pulled away when they charged. The result is that a phalanx rarely

encountered its opposite as a unified front.

For these reasons Thucydides (5.70.1) tells us that large armies break

their order are apt to do in the moment of engaging.

Thucydides (5.71.1)

also describes phalanxes drifting to the right as they advanced because men

sought to shelter their unshielded right side. This would have resulted from

men twisting their torsos to hold the aspis in front of them. But it is likely that the whole phalanx

contracted as well. Bunching as they

moved would have been a natural reaction of frightened men as it is with other

animals. The Strategikon, attributed to

Maurice (12B.17), describes the ease with which men can converge laterally just

prior to contact with the enemy. Two

approaching phalanxes would end up overlapping on the right through either

drift or contraction to the right, and the difference would be difficult to

tell. Men who began the charge at a

spacing of just over the diameter of their shields might now find that they

overlap to some degree with their neighbor’s.

Much of the order lost

during the charge could be regained as units reformed a battle line upon

contact with the enemy. The alternative

is that whole taxeis ran tens of meters past units next to them in line that

were engaged when the foes opposite were delayed or slow moving Spartans. The two phalanxes would have slowed as the

enemy loomed large. The same fear that

drove them to charge would keep them from running blindly into a hedge of enemy

spears. Because disorganized men charging at speed into the enemy results in a

weaker mass collision, there is no reason why men could not halt at spear range

rather than after crashing together. If

men did not regularly stop and fight with their spears, then it is difficult to

understand the many references to one phalanx breaking when the two had closed

to spear range. Hoplites converging at

even a modest 5 mph would cover this distance in less than half a second.

What followed was

described by Sophocles (Antigone, 670) as a “storm of spears”. While taunting their foes, the first two

ranks of the opposing phalanxes would assume the ¾ stance common to most combat

arts and strike overhand across a gap of about the 1.5 m reach of a dory. The overhand motion results in a much

stronger thrust than stabbing underhand (Connolly, 2001), and would be less

likely to impale the men behind. When

striking from behind a wall of shields, the overhand strike not only ensured

that your arm was always above the line of shields but allowed a wide range of

targets. During this combat adjacent

hoplites were mutually supporting, and a man could be killed through the

failure of those alongside him (Euripides, Heracles 190). The second rankers would have attacked where

they could reach, but their spears also acted to defend the men in front.

The aspis would have

been tilted up and toward the enemy.

With the shield snug on the forearm, this would be the natural result of

lifting the arm, but it also presents the maximum shield area to a downward,

overhand strike. In this position, the

shoulder doesn’t bear any of the weight because the centrally placed porpax

results in the lower half of the shield balancing the upper half with all the

weight on the arm. It can be braced

against the shoulder if pushed back by a strike.

Spear fighting could go

on for some time, and often one side must have given way as a result, but we

know that battles could move to close range.

It is difficult to imagine men easily forcing their way through multiple

ranks of massed spears, but we know that hoplites often broke their spears, and

a sword armed man would be highly motivated to close within the reach of his

foe’s spear. Perhaps this was easier as

fatigue set in. Once swordsmen closed

with the spearmen somewhere along the line, phalanxes could collapse into each

other like a zipper closing as spearmen abandoned their useless spears in favor

of their own swords.

It is now that rear

rankers could bring their pressure to bear.

They would close up swiftly, initially supporting those in front, but then

gradually pushing them tight together.

All ranks would now cover their chests with their shields. While this was occurring the front rankers

fought, and their blows could not miss (Xenophon, Anabasis, 2.1.16). Images of hoplites show a variety of strikes

that could be used with the upraised right arm over the shields. The so-called “Harmodios blow” is a high

slash from around the head that has been derided as useless, but here strikes

and parries up around the head would be the rule. Point heavy chopping swords would be useful

in othismos, but the short swords, often attributed to Sparta and seen on

stelai from Athens and Boeotia, would be deadly. A downward stab, alongside the neck, into the

chest cavity can be seen on a vase in the Museo Nazionale de Spina (T1039A).

The crowding of

othismos and periods of active, intense pushing could last for a long time as

men leaned ahead like weary wrestlers.

But the peak pressure is only maintained if the opposing phalanx chooses

to resist it. If they move back, their

foes have to pack-in tight again before maximum force can be transferred. All such moves have to start at the back of

the files, there is no point at which a man could simply jump back and his

enemy would fall forward. Just as

packing was gradual, so is unpacking.

The whole mass would move in spasms and waves like an earthworm. Increased file depth is an advantage in this

type of contest, but the answer to those who wonder how why at Leuktra 50 ranks

of Thebans didn’t immediately drive 12 ranks of Spartans from the field rests

in the difficulty in coordinating such deep files of men to push in unison and

the need to constantly repack as men advance.

Deep ranks function more like a wall behind those in front than an aid

is pushing forwards.

When hoplites could no

longer sustain the rigors of pushing, the rear ranks of the phalanx would turn

and flee. What followed could be a free

for all as men broke ranks to target the backs of routed foes. It is now that lessons of hoplomachoi,

martial arts masters, were of most use (Plato, Laches 182a). Men who had been holding up their arms

throughout battle would surely opt for underhand strikes at this point as seen

for single combat on many vases.

Hoplites did not press pursuit for long, so many saved their lives by

dropping their shields and spears and outpacing those chasing them. Safer still was making a stand with

compatriots and letting the victorious hoplites find easier prey as Socrates

did after Delium (Plato Symposium 221b).

Hoplite battle

encompassed both the storm of spears and press of shields, but by the late 5th

century clever generals were coming up with ways of exploiting the weaknesses

of both phases of combat. Envelopments

and ultra-deep formations took advantage of the weaknesses of armies set on

simply fighting a decisive battle with units arrayed opposite them, often with

little regard for flank protection. A

century later hoplites would lose their supremacy to Macedonian pikemen,

themselves up-armored skirmishers, who presented them with spears that far outranged

the dory and only a dense hedge of spear points to push against.

Paul Bardunias is an

entomologist working on self-organized group behavior in termites and

ants. His interest in ancient warfare is

hereditary, for his family comes from Sparta.

He is currently applying his scientific training to provide new insights

into hoplite combat at www.hollow-lakedaimon.blogspot.com. He is indebted to Russian hooligans, whose

tireless shenanigans allow us to witness the fluidity and spontaneous order

that arises in crowds of belligerent men (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dAk4dceoK4&feature=related).

J.K. Anderson, Military

theory and practice in the age of Xenophon.

Berkeley and Los Angeles 1970

P. Bardunias, ‘The aspis. Surviving Hoplite Battle’, in: Ancient Warfare I.3 (2007), 11-14.

G.L. Cawkwell, ‘Orthodoxy and Hoplites’, in The Classical Quarterly 39 (1989),

375-389.

P. Connolly, D. Sim, and

C. Watson, “An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Three Methods of Spear Grip

Used In Antiquity”, in: Journal of

Battlefield Technology, Vol. 4, No. 2, July 2001.

A.K. Goldsworthy, ‘The Othismos, Myths and Heresies: The Nature of Hoplite Battle’, in War and History 4 (1997), 1-26.

V.D. Hanson, The

Western Way of War. Oxford 1989.

V.D. Hanson (ed.), Hoplites. The Classical Greek Battle Experience. London and New

York 1991.

P. Krentz, ‘The Nature of Hoplite Battle’, in: Classical Antiquity 16 (1985), 50-61.

P. Krentz, ‘Continuing the othismos on the

othismos’, in Ancient History Bulletin

8 (1994), 45-9.

P. Krentz, D. Kagan and D.

Showalter, The Battle of Marathon.

Yale University Press (2010).

R.D. Luginbill, ‘Othismos:

the importance of the mass-shove in hoplite warfare’, in: Phoenix 48 (1994), 51-61.

L. B. Perkins, Crowd

Safety and Survival, Lulu.com, 2005

A. Schwartz, Reinstating

the Hoplite: Arm, Armor, and Phalanx Fighting in Archaic and Classical Greece.

Franz Steiner Verlag, 2010

H. van Wees, Greek

Warfare. Myths and Realities. London 2004.